I’m pretty fond of most of this series and this instructor.

Sunday, May 28, 2017

Thursday, May 25, 2017

Tuesday, May 23, 2017

Beards and Banjos

Seriously. If Minnesota music dweebs are this lame, imagine how incredibly awful the degraded species is in the southeast!

Tuesday, May 16, 2017

Why Bother?

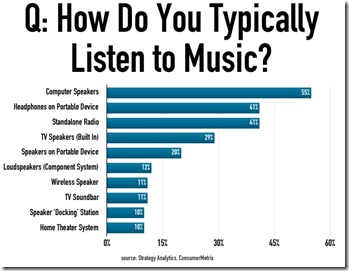

“Headphones connected to a portable device followed with 41% of respondents, alongside stand-alone radio, also with 41%. Surprisingly, TV speakers were also highly-ranked, with 29% ticking that box.”

While nothing about this information is surprising, that doesn’t keep it from being depressing. More out of habit and curiosity these days, I still read Mix Magazine, TapeOp, Recording, ProSoundWeb, and Pro Sound News. I’m mostly entertained by the seriousness audio “engineers” (an oxymoron if there ever was one) take their degraded “craft.” Almost by reflex, when I read an interview with some kid who has decided he’s the next incarnation of Tom Dowd (No, he won’t have the slightest idea who Tom Dowd was.) I chase down a few examples of the music he refers to as examples of his work. Invariably (Yes, I do know what that word means.), it will be some awful sounding collection of distortion, overused effects, trite synthesizers, and horribly recorded drums.

The critical feedback loop between musicians and their vanishing customers has been wreaked by “portable devices” and the delusional pipedream that some whackos have that high resolution audio will change any of that is nuts. I suppose I should be happy with the resurgence of vinyl, since you can’t get that shit on to a cell phone? If you know me, you know I think going back to vinyl is about as silly as abandoning cars for horses. It’s not the vinyl that matters, it’s the amplification and speaker systems, dumbasses.

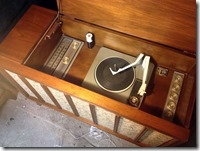

My mother had convinced him to buy an RCA console system, but he decided that took up too much room and it ended up in the basement, too. It really was pretty awful, but slightly better sounding than my Webcor.

By then, I had long since graduated to component stereo equipment, then band sound systems, and, finally, recording studio equipment for my home audio system. Our living room system (aka “Home Theater System”) is still a decent receiver and a pair of JBL studio monitors. The down side to that is that, if I bother to listen at all carefully, it’s pretty obvious that Pandora broadcasts in a mediocre MP3 format. Usually, I’m not that focused on the music coming from the living room when I’m working in the kitchen. When I am actually critically listening, I listen to CDs. I’ll put CD quality over vinyl any day.

Too often, when someone under 30 wants to show me some music it will be demonstrated on a cell phone speaker. I have no idea what I’m supposed to get from that experience. I can usually pick out the melody and determine if it is a male or female lead voice. That’s about all I’m willing to invest in that miserable fidelity source, though, which is often disappointing to the person trying to impress me.

To be truthful, if you are a cell phone user I have to suspect you don’t care about fidelity in any form. While I haven’t had a fixed-line telephone for quite a few years, our primary telephone looks a lot like a fixed-line system. Our phone service is provided through our high-speed ISP and an Ooma Tele. The sound quality was a substantial step-up from the fixed-line system provided by Qwest and, later, Comcast in our Twin Cities home. I can, in a few moments, tell if a caller is on a cellphone because the quality is miserable. Always. My guess is if you can tolerate that level of distortion in a voice conversation you aren’t that discerning in any aspect of audio. So, while I’m not surprised that music is being listened to on actual speakers by an audience of 12%-and-shrinking I’m also not impressed by your musical tastes. Your opinion of audio quality is just going to make me laugh, so don’t waste either of our time.

Monday, May 15, 2017

“But Everybody Does It This Way!”

Early in my life, in 1956 when I was 8, I’d been exposed to the totally nutty propaganda regarding Elvis Presley, "50,000,000 Elvis Fans Can't Be Wrong." In fact, I was pretty sure by the time I was 10 years old, that all Elvis fans were idiots. Elvis vs. the Everly’s? Even Ricky Nelson? No contest. Later, when I got much further into music, specifically, jazz at the ripe old age of 13, I scored Elvis fans of all sorts as something less than sentient: or worse, they were emotional. As I began to think of myself as a musician (As irrational as that was, I know.) and broadened my listening palette to R&B and some classical music, the Beatles came along and blasted pretty much everything of any sort of complexity off of the AM radio band. Of course, that lowered my opinion of “everybody” to something a few notches below farm animals.

Over the course of my career, the “everybody does it this way” explanation has regularly been applied to all sorts of stupid things. Live sound system setup, for example. “Everybody” seems to think the hot sequence of events for a large or small scale sound system is to waste time getting everybody happy with the monitor system, then turn on the Front of House (FOH). One of my favorite moments in Crazy Heart came 47:28 into the movie. Jeff’s character stops the rehearsal and tells the FOH jackass, “I need kick and snare, turn down the damn guitars, you’re drownin’ out the lyrics.”

The sound jackass says, “The mix is good man. You can’t hear what I’m hearin’ out here.”

Jeff’s guy says, “Yeah, you’d be surprised. Do it the way I tell ya and leave it.”

Asshole says, “The mix is just fine, man. Trust me on this.”

Jeff says, “No. I’m an old man. I get grumpy. You heard me.” And aside, mostly to himself says, “Damn sound man. The try to fuck up the opening act. . . ” And you should listen to the rest of the conversation. Jeff became my hero in that movie.

The way 99.99…% of shows are mixed wouldn’t pass for a first attempt right out of high school for a recording engineer. A big part of the problem is that the kiddies and functionally-deaf assholes who pass for “sound men” think the monitor system is more critical than the FOH system, so they setup monitors first and there is no coming back from that fatal move.

A few weeks ago, I had the opportunity to record a variety of live performances at the local theater. Because we still haven’t managed to find the time to get the overly complicated and bureaucratic DiGiCo drivers to work with any recording program, I was stuck using my six channel Zoom H6 recorder for more than a dozen different acts from folk singers to a 22-piece horn section with a rhythm section. Did I mention, only six channels?

I would be left with only one channel to dedicate to the occasional drum kit and rarely more than two on most of the acts. One of my favorite techniques is often referred to the Glyn Johns’ technique. Another excellent tactic is to place an X-Y pair behind the drummer’s head, simulating the “mix” the drummer is creating for himself. Sometimes a kick mic is useful, but for really excellent drummers I often end up barely using it or not at all. So, with only one channel to spare I put a single condenser in that position. The end result even surprised me. With only a little EQ, mostly a low end bump, the end result was a good full drum kit sound with excellent (considering the stage volume) isolation. Obviously, this tactic puts the “control” of the drum mix in the hands of the drummer. Less obviously, I think that is a good thing. I have generally found that good drummers have a better idea of what their playing sound sound like than 99-something-percent of recordists, including myself.

I would be left with only one channel to dedicate to the occasional drum kit and rarely more than two on most of the acts. One of my favorite techniques is often referred to the Glyn Johns’ technique. Another excellent tactic is to place an X-Y pair behind the drummer’s head, simulating the “mix” the drummer is creating for himself. Sometimes a kick mic is useful, but for really excellent drummers I often end up barely using it or not at all. So, with only one channel to spare I put a single condenser in that position. The end result even surprised me. With only a little EQ, mostly a low end bump, the end result was a good full drum kit sound with excellent (considering the stage volume) isolation. Obviously, this tactic puts the “control” of the drum mix in the hands of the drummer. Less obviously, I think that is a good thing. I have generally found that good drummers have a better idea of what their playing sound sound like than 99-something-percent of recordists, including myself.

Wednesday, May 10, 2017

Organization? We Don’t Need No Stinkin’ Organization

I have a pair of Electro-Voice RE-18’s in the shop that need, I hope, minor repair. The RE-18 was one of the best handheld vocal microphones ever made by anyone in audio history. That’s my opinion and I’m sticking with it because I’ve owned about a dozen of these amazing tools and everyone has been terrific. Every vocalist I’ve taught to use the RE-18 has taken to the microphone like it was a revelation. Every FOH engineer I’ve convinced to try the RE-18 has fallen in love with the mics. Obviously, the RE-18 was doomed to failure in an industry where the SM58 is considered “good enough” when it is obviously barely competent as a talkback mic or a taxi company dispatcher’s desk mike.

When I wrote EV’s misnamed “Technical Services” about obtaining repair parts for the RE-18, the response was, “Unfortunately, we no longer have parts or service to support this series." Although this was a very good mic it was discontinued around 1990.” I, of course, knew all of that except for the non-existent parts supply and EV’s arbitrary decision to discontinue their lifetime warranty, “Also, these microphones are guaranteed without time limit against malfunction in the acoustic system due to defects in workmanship and material.” [Words taken right from the RE-18’s Product Manual.] That warranty was one of the reasons EV was able to ask a premium price on all of the RE Series microphones: $350 back when an SM58 had a street price of $75. Bosch, a German company, has no clue how to deal with customer service, manage quality, or produce a competent product: a typical condition for German companies. Nothing new here. If a German company didn’t totally hose up customer service functions, I’d be suspecting someone else actually owned the company.

EV does, however, still make and sell the RE-16. Many of the RE-16;s parts are identical or close enough for practical purposes. After going around via email with the “we no longer have parts or service” Tech Service guy, I called Tech Services today. Same song and dance, except this guy knew he didn’t know much and really, really wanted to transfer me to “Parts.” Usually, I have had to go through Tech Service to get part numbers and/or assembly drawings. At EV/Bosch, Tech Service has none of that. In fact, I have to wonder what technical services Tech Services can provide without actual product information at hand.

Lucky for me, the woman who answered the parts call was, essentially, an actual Tech Services technician. We quickly identified the parts I wanted to buy, she priced them, she told me when I’d receive those parts (about 14 days), and took my order.

Friday, May 5, 2017

Gratitude Is Dead?

In 1971, I was about to be a new dad, had an incredibly demanding but low paying tech job, and was stranded in one of the planet’s armpits, Hereford, Texas; where when the world gets an enema, that’s the place the tube goes. I needed money and there weren’t a lot of options for decent payinjg 2nd jobs in that place at that time. So, I talked to a couple of Amarillo music stores and my local store and began a music equipment/instrument repair service. Fairly quickly, I learned two things: 1) music stores rarely pay their bills and 2) musicians are even less likely to pay bills. No surprise, right? It was for 23 year old me, right out of tech school and at one of the many “I’m outta here (music)” points in my life.

The truth is that it isn’t fair to imply that ALL musicians didn’t pay their repair bills. In fact, I became a regular stop for the many Mexican bands in the area and they paid their bills like clockwork. Country Western dicks, on the other hand, were reliably unreliable. They were gods of “if you let me take my amp today, I’ll gladly pay you on Saturday after the gig.” Not once did that ever happen. There weren’t many rock bands in 1970’s west Texas, but the ones that were there were only slightly less bogus than the C&W assholes. Most of the rock guys were high school kids, so I should probably cut them some slack but I was barely out of high school and I had a family to support. So fuck ‘em.

Lucky for me, I was on a mailing list from Don Lancaster, the future author of The Incredible Secret Money Machine, and his newsletter taught me some of the things that would be key to my businesses for the rest of my life. Rule #1: “Know the difference between cold cash, j-dollars, and megabucks.” “j-dollars” are the engineering business term for imaginary money. The rule for megabucks is “the odds of you ever getting one red cent are invariably much lower than you think.” Those rules stuck with me, especially after two years of wrestling with musicians and music stores for the money they owed me. The cap on that money in my business career came after I had a spare room filled from floor to ceiling with repaired equipment that had yet to be paid for and I was about to leave Texas for a new job in central Nebraska. I posted a notice in the local paper and sent post cards to the customers who had given me legitimate addresses warning them that I would be selling all of the customer equipment in my shop for the repair bills. Of course, everyone thought I was bluffing and one weekend I emptied the spare room and the following Monday we were on the road north.

When I canned the acoustic consulting and the audio equipment repair businesses, an energetic, personable, and talented young man caught much of what I was tossing off. He gave me a lot of crap for bitching about how little I liked working for musicians and how much I hated the billing hassle. Less than six months later, he quit the work too, saying, “I can’t believe it took you so long to quit doing that shit.” I know what you are saying, kid.

As much of a hardass as all that makes me sound, the fact is that I have done shitloads of work that I’d have rather avoided. Repair works is rarely fun and often miserable. I used to tell my studio maintenance students, “Get used to being wrong a lot if you want to do repair work. If you are really good, you’ll be right one our of ten times.” That is not as much fun as it sounds. Along with busted stuff and lousy designs kicking my ass for 40 years, a lot of the work I did was just grunt work: equipment installation, studio wiring, CAD/CAM programming, debugging other engineers’ designs, and politics. Most of it was better than a sharp stick in the eye and some of it paid better than being a slave, but if I could have been a rock star or a trust fund baby I’d have picked those options in a heart beat.

Now that I’m retired, I’m doing all sorts of bullshit work around our house, volunteering to run sound, recording music, helping with construction or design projects, and some of the silly crap I’ve done my whole life that probably deserves the label “hobbies.” My general rule for considering a project, today, is “If I like it, I’ll do it for free. If I don’t, you can’t afford me.” That offends some people. They think I’m being an asshole for not working cheap, now that I have the spare time, especially since I do some work for free and it all looks the same to them. Learning how to say “no” took me most of my life and it still makes me very uncomfortable. However, that’s what I’m saying more often than not these days and I’m getting better at it. The day I don’t feel compelled to explain why I don’t want to record your awful music, run sound for your awful sounding cover band, make you a guitar, fix your computer, guitar amp or home stereo equipment, build you a wall or a fence just like the one I just built for my wife, help you roof your house, or whatever, will be the day I am officially comfortably retired. Until then, I’m still practicing with the “no word” and if it looks unnatural on me, it is.

Tuesday, May 2, 2017

The High Cost of Doubt

When I was a working engineer and, later, an engineering manager, my least favorite answer to any question was always, “Because everyone does it that way.” For the last 50 years, a mantra of mine, and my current email signature, has been a Bertrand Russell quote, “The fact that an opinion has been widely held is no evidence whatever that it is not utterly absurd; indeed in view of the silliness of the majority of mankind, a widespread belief is more often likely to be foolish than sensible." More than often this is true, but occasionally my kneejerk reaction to convention takes me, the hard way, through the processes that others have already explored and I discover sometimes things are always done pretty much the same way for a reason. Sometimes that reason is bullshit, but there is often a core assumption to be evaluated that with my limited-to-non-existent visual skills I can not see until I experiment.

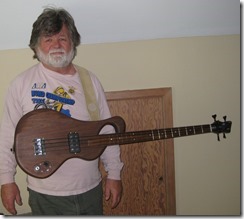

My baseline bass is a Steinberg L-Series headless and almost body-less bass. I’ve owned a couple of these instruments in the last thirty years and, currently, own and play a Hohner knock-off of this bass. I love everything about my Hohner from the low weight to the perfect balance to the sound. The only thing I don’t love is the look, which is always a heavily enameled solid color body and neck with a rosewood fingerboard. If the guitar is going to be made from wood, which my Hohner is and my Steinbergers were not. The headless design was not an option for the first year guitar design course. One of the failures from my acoustic guitar build was my original intention to make my instrument from all-domestic wood. I screwed up my first two walnut fingerboards and my one-piece walnut neck block and had to start over quickly, so I snagged a slab of quarter-sawn rosewood and a mahogany neck block from a guitar builder who was dumping material stock cheap and those two critical parts of the instrument ended up coming from imported wood.

This time, I wanted to avoid that and my design was for all walnut; partially because I love the look of walnut and partially because I wanted to take a second look at a design I started almost 40 years ago. That design was based on the B.C. Rich Mockingbird body and incorporated a fretless Fender Precision neck. Considering my rookie woodworking status, that instrument came out pretty well, except that it weighed close to 50 pounds. I started with a 2” thick piece of old growth walnut that I’d milled myself from rough walnut stock I’d found in a friend’s barn. For my current instrument, I wanted everything I’d accomplished with that original instrument without the physical stress. Literally, my bandmates called my old bass “the refrigerator” because between the bass and the Star roadcase, hauling that thing up a flight of stairs was a lot like carrying a refrigerator with one hand. It currently resides in my daughter’s music room where no one has played it for decades. Honestly, it was a terrific bass, sonically, but it will cut a groove in your shoulder that will bisect the player if given enough time.

The picture at left shows what balanced looks like. The guitar hangs perfectly neutral when the neck is parallel to the ground. This sort of defeats about 50% of the reason I designed in that “handle” at the top of the instrument, but I thought balance was more important than justifying my design geekiness. Turns out, balanced is not particularly comfortable in a bass, at least for me. While my Steinberger/Hohner L-Series instruments are, in fact, balanced, a slight increase in headstock weight makes a body-heavy strap positon a lot more desireable. For one, I have short limbs (and fingers) and I end up pulling the neck up and slightly to my right when I play the bass. So, I repositioned the neck pin as far up that “handle” as possible, which is pretty much exactly where everyone else on the planet puts a neck strap pin. The end result was a much more comfortable balance and a more relaxed playing position. Which, of course, everyone who has built an electric guitar in the last 75 years knew before I decided to test traditional thinking.