Quite a while ago, a friend recommended that I watch the 2016 PBS series “Soundbreaking, Stories from the Cutting Edge of Recorded Music.” At that time, I gave it a show by watching the segments on the PBS website and gave it up as a bad experience, mostly because the PBS webpage was a pain in the ass and I’ve never subscribed to cable television. The reminder came around again this past week and I finally hunted the series down on DVD from my local library. It was worth it.

Quite a while ago, a friend recommended that I watch the 2016 PBS series “Soundbreaking, Stories from the Cutting Edge of Recorded Music.” At that time, I gave it a show by watching the segments on the PBS website and gave it up as a bad experience, mostly because the PBS webpage was a pain in the ass and I’ve never subscribed to cable television. The reminder came around again this past week and I finally hunted the series down on DVD from my local library. It was worth it.

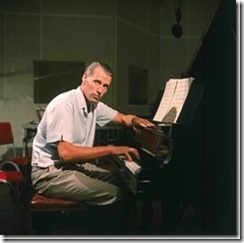

I should have known it would be worth the effort, since one of my heroes, George Martin, was the show’s producer. It was Sir Martin’s last projects and one worthy for a career cap of one of the most competent, creative, and original people ever involved in music and recording. While I’ve never been much of a Beatles fan, I have always been a George Martin fan. When Lennon was throwing his poncy hissy fit about Martin being the “5th Beatle,” Lennon said, “When people ask me questions about 'What did George Martin really do for you?,' I have only one answer, 'What does he do now?' I noticed you had no answer for that! It's not a putdown, it's the truth," I, immediately thought, “What about ‘Blow by Blow’?” Lennon would never sit in a recording studio that accomplished that much from his first day to his last. But, I was never a Beatles fan, so what do I know? I am, however, a lifetime Jeff Beck fan and, lucky for me, there are a few Jeff Beck interviews in the series.

I should have known it would be worth the effort, since one of my heroes, George Martin, was the show’s producer. It was Sir Martin’s last projects and one worthy for a career cap of one of the most competent, creative, and original people ever involved in music and recording. While I’ve never been much of a Beatles fan, I have always been a George Martin fan. When Lennon was throwing his poncy hissy fit about Martin being the “5th Beatle,” Lennon said, “When people ask me questions about 'What did George Martin really do for you?,' I have only one answer, 'What does he do now?' I noticed you had no answer for that! It's not a putdown, it's the truth," I, immediately thought, “What about ‘Blow by Blow’?” Lennon would never sit in a recording studio that accomplished that much from his first day to his last. But, I was never a Beatles fan, so what do I know? I am, however, a lifetime Jeff Beck fan and, lucky for me, there are a few Jeff Beck interviews in the series.

Some of the show’s highlighted producers, like Phil Spector, would naturally put me off because the records the show is celebrating from Phil and his ilk are records I have never liked much. Spector’s “Wall of Crap” sound always made me wish my stereo was quieter and of lower quality. Every single record he ever recorded made me wish someone had been able to tell Spector “that’s enough crap, stop while you are ahead.” Never happened, until the police finally delivered that message after he murdered an actress in 2003. Lennon brought Spector in to trash-up “Let It Be” and I never had much use for that record until “Let It Be, Naked” came out in 2003. That record stripped off the Spector crap and demonstrated the power of George Martin’s arrangements and engineering at the peak of that band’s capabilities. As Martin said when he was asked about the credits for “Let It Be,” “How about ‘produced by George Martin, over-produced by Phil Spector?”

The segments on Dr. Dre, Sly Stone, Les Paul, Jeff Beck, Al Schmidt, Tom Scholtz, Don Was, Brian Wilson, Marvin Gaye, etc. paid the viewer-bill, for me. The series is a terrific primer on the history of recording technology and, more importantly, the people who pushed the technology to its limits. It was especially fun to see Giles Martin, George’s son, playing with the old EMI console. Watching him reproduce segments of “Revolver;” “Tomorrow Never Knows” makes it pretty clear how much George Martin, Geoff Emerick, and the EMI engineers contributed to the sound we describe as “The Beatles.” Of course, John Lennon never approached that level of greatness again, but George Martin did.

The series episode titles tell you a lot about what you will see and hear:

- Episode One: The Art of Recording.

- Episode Two: Painting with Sound.

- Episode Three: The Human Instrument.

- Episode Four: Going Electric.

- Episode Five: Four on the Floor.

- Episode Six: The World is Yours.

- Episode Seven: Sound and Vision.

- Episode Eight: I Am My Music.

In this day of hyper-expensive microphones and zillions of digital plug-ins and analog or digital effects, it’s hard to imagine that many of the records today’s artists hope to equal were done using incredibly limited equipment and downright cheap dynamic microphones (many of them omnidirectional). Practically every home studio in the country has better and more powerful technology, more available tracks, easier access to instruments and sounds, and no excuse for not making equal or better music; except for the talent problem. The “Painting with Sound” segment does a wonderful job of describing how many of the great pop records were made: warts and all.

One of the series’ silly aspects, technology, was often highlighted by having Ben Harper explain a variety of technologies. Ben is a fine performer, but what he knows about electronics, acoustics, or technology in any form could be well-documented on a single fingernail with a relative coarse Sharpie. His “thoughts” were good for a laugh, though. There are a few other moments like that, but there are plenty of technically-sound moments to spell the laughter: Tom Scholtz, for example, Les Paul, Al Schmidt, Don Was, and more than a few other recording greats.

I almost held my breath through “I Am My Music,” waiting for the usual MP3 snobbery and I was really surprised and pleased with the absence of all that silliness. Mostly, my experience with ABX testing and audio repair work makes me really suspicious of “pros” who make claims to golden ear-ed-ness. But we didn’t have to listen to any of that here because the focus of the episode was about how the MP3, digital downloads, and the industry’s shortsightedness caused the music business to go into freefall; for good reasons.

Do NOT forget to watch the “extras” on the 3rd DVD.

I have a theory that a rational society would determine income levels by the contribution made by each citizen. So, the highest paid people would always be those who society could, literally, not live or thrive without: farmers, scientists, physicians, engineers, technicians, firemen/persons, sanitation workers, plumbers, electricians, carpenters, and so on. The people who get paid the most are the ones who would be missed the most if they vanished from the planet. Bankers, hedge fund banksters, lawyers, Republicans, actors and television/movie people, professional athletes and artists, etc. get paid the least because no one would notice them missing if they were to vanish. Their jobs would be filled immediately by perfectly untrained and sufficiently skilled people who would also be paid minimum wages.

I have a theory that a rational society would determine income levels by the contribution made by each citizen. So, the highest paid people would always be those who society could, literally, not live or thrive without: farmers, scientists, physicians, engineers, technicians, firemen/persons, sanitation workers, plumbers, electricians, carpenters, and so on. The people who get paid the most are the ones who would be missed the most if they vanished from the planet. Bankers, hedge fund banksters, lawyers, Republicans, actors and television/movie people, professional athletes and artists, etc. get paid the least because no one would notice them missing if they were to vanish. Their jobs would be filled immediately by perfectly untrained and sufficiently skilled people who would also be paid minimum wages.