The “ . . . “ in the title is a “fill-in-the-blank” space for whatever it is that you are wrestling with that sounds awful": my band, my club/bar/restaurant, my living room, my recording studio, my practice room, my auditorium/church/theater, etc. The answer to that question is almost always “room acoustics,” except when the answer is “you suck.” I can count on the fingers of my hands the number of performance places I’ve worked or visited that weren’t acoustic disasters. On top of that, even the places that were acoustically decent were often wreaked by a poorly installed or inappropriate sound system. So, most often those two problems are enough to make a performance intolerable or disasppointing.

Room acoustics are tough to overcome. Lots of bars, for example, are reflective, resonant, reverberant disaster zones. There are extreme limits to the options for fixing that kind of room. Often, the closest thing to a fix is to deaden the room with lots of absorption. However, most types of absorptive material also absorbs smells and is relatively fragile; not ideal for a typical bar that serves food. Worse, the biggest problems in most rooms will be the room modes (resonances) and non-ideal reflection points (hard and flat or hard and concave surfaces, for example). Room modes are usually very low frequencies that resonate in a room like the pitch of a bell or drum. The treatment for that kind of energy and frequency requires lots of space for absorption; with the same problems as regular absorption materials.

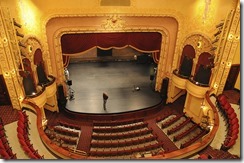

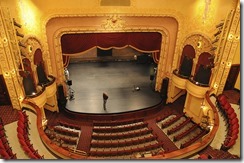

The shape of some rooms is impossible to overcome and there is no point in attempting to spend any money making those rooms better because it will just be good money after bad. A lot of historic theaters—Red Wing’s Sheldon Theater or Saint Paul’s Fitzgerald Theater and most pre-1980’s churches, for example—are particularly unsuited for modern music. That is also true for practically every auditorium on the planet. Architectural features that include domed roofs or concave faces are particularly miserable acoustic problems. If those featurers are deemed “historic,” there is no hope for a fix from any amount of audio equipment or design. Those beautiful curved surfaces create focused reflections that are powerful, narrow

The shape of some rooms is impossible to overcome and there is no point in attempting to spend any money making those rooms better because it will just be good money after bad. A lot of historic theaters—Red Wing’s Sheldon Theater or Saint Paul’s Fitzgerald Theater and most pre-1980’s churches, for example—are particularly unsuited for modern music. That is also true for practically every auditorium on the planet. Architectural features that include domed roofs or concave faces are particularly miserable acoustic problems. If those featurers are deemed “historic,” there is no hope for a fix from any amount of audio equipment or design. Those beautiful curved surfaces create focused reflections that are powerful, narrow  band, and predictable only at the focal point. From every other angle the reflection point will be complicated by other architectural features and their reflection pattern. The end result of this kind of reflection problem is that every spot in the room sounds different. Usually, dramatically different. Any problem has a solution, but acoustic solutions are expensive and in a historic building their application is limited by the historical value of the original, flawed design. Since the most noticable reflections from these features is often mid and low-mid frequencies, it is possible to camoflauge absorption materials inside the curved features. Often the tactic is to used perforated panels covering layers of absorptive material and covered by cloth painted to resemble the historic artwork. Many historic facilities have created large absorption areas at the back of each level of the room. Sometimes a row of seats has to be sacrificed to obtain decent room reflection and modal control, but the sacrifice opens the room up to a broader pallet of performances.

band, and predictable only at the focal point. From every other angle the reflection point will be complicated by other architectural features and their reflection pattern. The end result of this kind of reflection problem is that every spot in the room sounds different. Usually, dramatically different. Any problem has a solution, but acoustic solutions are expensive and in a historic building their application is limited by the historical value of the original, flawed design. Since the most noticable reflections from these features is often mid and low-mid frequencies, it is possible to camoflauge absorption materials inside the curved features. Often the tactic is to used perforated panels covering layers of absorptive material and covered by cloth painted to resemble the historic artwork. Many historic facilities have created large absorption areas at the back of each level of the room. Sometimes a row of seats has to be sacrificed to obtain decent room reflection and modal control, but the sacrifice opens the room up to a broader pallet of performances.

The go-to solution for many facilities has been to spend even more money on sound equipment under the delusion that loudspeakers and electronics can power overwhelm the acoustic flaws. Louder is only louder. Better has nothing to do with volume and, usually, better is completely defeated by volume. The magic of speaker arrays has been grossly oversold and the physics behind array designs is usually ignored because the positive effects are inconveniently limited. For example, in the picture to the left, Meyer’s MILO array in the 3-cabinet (2m tall) application at the top of the illustration is fairly vertically directional at the 1kHz frequency illustrated.

The go-to solution for many facilities has been to spend even more money on sound equipment under the delusion that loudspeakers and electronics can power overwhelm the acoustic flaws. Louder is only louder. Better has nothing to do with volume and, usually, better is completely defeated by volume. The magic of speaker arrays has been grossly oversold and the physics behind array designs is usually ignored because the positive effects are inconveniently limited. For example, in the picture to the left, Meyer’s MILO array in the 3-cabinet (2m tall) application at the top of the illustration is fairly vertically directional at the 1kHz frequency illustrated.  As the frequency decreases, the verticle dispersion pattern will widen until it is omnidirectional a little below the half-wave length diameter of the largest driver (30cm, or about 500Hz). As the frequency increases, those “beams” of acoustic power dispersion vary in direction and intensity, as you can see from Meyer’s illustration of verticle splay and coverage. Not only does an array’s “steering” capability depend on a large number of drivers and substantial array height to control dispersion range, but even with the most expensive array processors and ideal speaker mounting location (rarely available) the idealized verticle speaker control is pretty much sabotoged by the less convenient and unpredictable horizontal polar pattern. Personally, I’d give no more creditability to this manufacturer’s (Meyer Sound) below-500Hz dispersion patterns than Trump’s estimate of his own personal wealth. In some areas, wild optimism is probably of some value. Here, it is just more marketing drivel in a field overly-contaminated with marketing drivel.

As the frequency decreases, the verticle dispersion pattern will widen until it is omnidirectional a little below the half-wave length diameter of the largest driver (30cm, or about 500Hz). As the frequency increases, those “beams” of acoustic power dispersion vary in direction and intensity, as you can see from Meyer’s illustration of verticle splay and coverage. Not only does an array’s “steering” capability depend on a large number of drivers and substantial array height to control dispersion range, but even with the most expensive array processors and ideal speaker mounting location (rarely available) the idealized verticle speaker control is pretty much sabotoged by the less convenient and unpredictable horizontal polar pattern. Personally, I’d give no more creditability to this manufacturer’s (Meyer Sound) below-500Hz dispersion patterns than Trump’s estimate of his own personal wealth. In some areas, wild optimism is probably of some value. Here, it is just more marketing drivel in a field overly-contaminated with marketing drivel.

So, if your situation is that you can’t avoid your room’s non-ideal reflection surfaces and you can’t overwhelm your room’s resonsances with any sort of speaker design. The chances are good that you probably can’t afford either the treatment cost or the cost of the lost real estate for appropriate acoustic treatment. If that is true, you’ll probably resort to the usual loud and irritating tactic most bars and theaters employ and that will drive away some customers and others won’t know the difference because that is the kind of abuse they’re used to experiencing. However, if you read and understood this paper you will at least know why your . . . sounds so awful.

No comments:

Post a Comment