In late 1991, I left my job at QSC Audio Products and my 9 year career with that company for what turned out to be one of the dumbest career and relocation moves I could have possibly made. My tolerance for high density overpopulation and the Southern California pace had played out. A couple of QSC’s direct competitors had been trying to recruit me for a year or so and one company that was in a slightly different audio market made me an offer I decided not to refuse. That resulted in the shortest period of employment in my 55 year career; 30 days. The manufacturing leg and my office for my new employer were in Elkhart, Indiana and the headquarters were in Chicago. No decisions could be made without several meetings in the Chicago office and most decisions were undermined by the office politics that took place after I had returned to Elkhart. After what seemed like an infinite number of pointless meetings and product and production decision reversals and constantly shrinking mismanagement expectations and commitments, I began to suspect my employment with the company was a mistake. So, I expressed a little of my frustration to the CEO, “I’m surprised a $50M company has so many more financial limitations than a $25M company (my previous employer).”

He said, “What makes you think we’re a $50M company?”

“That’s what you had told me in the cover letter that came with your employment offer.”

“I guess that proves you can’t believe everything you read.”

I thought about that conversation on the way back to Elkhart, collected my test equipment and personal belongings from my office that evening, and wrote a letter of resignation that night. The next day I started shipping resumes to everyone I thought might be interested in my skills and experience, including both of those companies that had been interested before I moved to Indiana.

Within a few days, I had lined up interviews with a Bose design site in Michigan, a medical device company in Denver, Sony in San Diego, Underwriter’s Laboratory in Chicago, Audio Precision in Oregon, and Crown Audio in Elkhart, Indiana. I didn’t leave California with a lot of resources and quitting my new job on such short order meant Unemployment Insurance wasn’t an option, so time was fairly critical. I did phone and in-person interviews with UL, Bose, the Denver medical device company, and Crown by the end of my first full unemployed week. Crown called to setup a second interview for the end of the next week. Early that week, I received firm offers from the medical device company and Bose and both companies wanted a decision from me on fairly short order. For mostly personal reasons, I decided to accept the Denver offer on Thursday. I have liked Denver and loved Colorado since I was a kid. I was a little lonely and a good friend (who I would be working with) offered to put me up in his home for as long as I wanted to stay. Finally, the opportunity to work in an entirely new-to-me industry was an interesting challenge. Partially out of curiosity, I went back to Crown on Friday for the 2nd interview.

The Manufacturing Engineering Manager, whose name I have long forgotten, brought me into a fairly large corporate meeting room that was lined with poster paper full of relationships, responsibilities, activities, anticipated results and achievements, and likely advancement possibilities. Crown’s management had put more effort into my possible employment with the company than the management all of my previous 25 years of work. What followed was an interesting interview with a half-dozen managers and another half-dozen people I’d be working with or who would be working for me. I was a little more blunt and honest in my answers to their questions, since I was pretty committed to the Colorado offer I’d already conditionally accepted and to getting the hell out of Indiana (a generally low income state that could be the poster child for economical inequality). I hadn’t yet received the written details to the Colorado offer and the formal offer, so I could still change my mind without too much guilt and I could discuss the possible Crown job without feeling like I was wasting their time.

On Monday, the Denver job offer arrived in the mail with a Wednesday decision deadline. I hung on to it until a little before the end of the work day Wednesday and called to accept that job. My new employer sent a moving van for my stuff the next day and I was on the road to Denver Thursday evening. Friday night, I was camping in southern Illinois and called my wife in California to check in. She said someone from Crown had called and really wanted to talk to me, leaving a home number. It wasn’t that late, so I called the number and discovered that Crown had tried to contact me in my Elkhart apartment that afternoon to make a very generous offer of employment. I had to tell him I was “taken” and wouldn’t be coming back to Indiana any time soon. He sounded disappointed, but I had warned them my decision was time-sensitive and that there were lots of factors that would determine my next career move.

On Monday, the Denver job offer arrived in the mail with a Wednesday decision deadline. I hung on to it until a little before the end of the work day Wednesday and called to accept that job. My new employer sent a moving van for my stuff the next day and I was on the road to Denver Thursday evening. Friday night, I was camping in southern Illinois and called my wife in California to check in. She said someone from Crown had called and really wanted to talk to me, leaving a home number. It wasn’t that late, so I called the number and discovered that Crown had tried to contact me in my Elkhart apartment that afternoon to make a very generous offer of employment. I had to tell him I was “taken” and wouldn’t be coming back to Indiana any time soon. He sounded disappointed, but I had warned them my decision was time-sensitive and that there were lots of factors that would determine my next career move.

I left Indiana in mid-November and didn’t have to be at my new job until January 2 and my new employer had provided me with a signing bonus and moving allowance so I wasn’t even in much of a hurry to get to Denver. The friend I’d be staying would be available to receive the moving van, so even making sure my stuff arrived intact wasn’t pressing. I took a full month to get from Indiana to Denver and, other than a little recording engineering and occasionally music equipment repair business, I was out of audio for the next decade. I never forgot the impression Crown made with me, though. I honestly felt like I’d been working in a poorly equipped garage at QSC for the previous 9 years, Crown felt that much more substantial and organized than we’d been while I thought we were their most serious competitors.

So, when I read that Crown had been absorbed in 2000 by the music business’ brain-drain conglomerate, Harmon, I was both disappointed and glad I’d passed on the Crown job. Honestly, other than Crown there wasn’t much about Indiana that appealed to me. I might not have lasted long there. Harmon was purchased by Samsung Electronics last November and the writing was on the wall for Elkhart before that depressing news. This month, when I read that Crown was closing the Indiana facility doors for good and only 115 jobs were affected, I have to admit I felt more than a little sadness. When I interviewed with Crown, I’d guess the facility employed at least 500 people. More importantly, there were a lot of decent, hard-working, competent people making and designing Crown products in 1991 and I hate to think that their efforts were wasted.

So, when I read that Crown had been absorbed in 2000 by the music business’ brain-drain conglomerate, Harmon, I was both disappointed and glad I’d passed on the Crown job. Honestly, other than Crown there wasn’t much about Indiana that appealed to me. I might not have lasted long there. Harmon was purchased by Samsung Electronics last November and the writing was on the wall for Elkhart before that depressing news. This month, when I read that Crown was closing the Indiana facility doors for good and only 115 jobs were affected, I have to admit I felt more than a little sadness. When I interviewed with Crown, I’d guess the facility employed at least 500 people. More importantly, there were a lot of decent, hard-working, competent people making and designing Crown products in 1991 and I hate to think that their efforts were wasted.

At one time, Crown was the only target in our sights at QSC. They were the industry leaders and everyone else was at our level or below. Go back to the late 1960’s and Crown’s DC300 solid state power amp was the only serious pro power amplifier game in town. Crown was an innovative, trustworthy, and decent American company and there is nothing good to say about the death of that sort of business. There aren’t many left and as the US continues to de-evolve into a minor 3rd world industrial power there will be a whole lot fewer in our future.

At one time, Crown was the only target in our sights at QSC. They were the industry leaders and everyone else was at our level or below. Go back to the late 1960’s and Crown’s DC300 solid state power amp was the only serious pro power amplifier game in town. Crown was an innovative, trustworthy, and decent American company and there is nothing good to say about the death of that sort of business. There aren’t many left and as the US continues to de-evolve into a minor 3rd world industrial power there will be a whole lot fewer in our future.

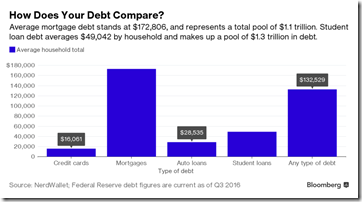

These days, most Americans are “conservative”; which is another way of saying that we are terrified of pretty much everything, especially ideas. The only thing we appear to be fearless in the face of is debt. Our president is a king of leveraged fake “wealth” and many Americans appear to admire Trump’s willingness to pretend to be rich in the face of constant business and investment failure. The US median household owes around $140,000, pays about $1,300 in annual credit card interest, and even the over-65 crowd’s median savings is well under $100k while middle-aged Americans average about $25k in savings. There is nothing conservative about those numbers.

These days, most Americans are “conservative”; which is another way of saying that we are terrified of pretty much everything, especially ideas. The only thing we appear to be fearless in the face of is debt. Our president is a king of leveraged fake “wealth” and many Americans appear to admire Trump’s willingness to pretend to be rich in the face of constant business and investment failure. The US median household owes around $140,000, pays about $1,300 in annual credit card interest, and even the over-65 crowd’s median savings is well under $100k while middle-aged Americans average about $25k in savings. There is nothing conservative about those numbers.